The Historical Importance of the Present

Minnesota Vernacular Visual Expressions 1988-1994: Storefronts, Signage, Yard Art

I transplanted from Madison, Wisconsin to Saint Paul, Minnesota in the middle of a frigid February in 1988. I loaded my brand-new Honda Civic hatchback to the roof and drove 250 miles northwest on Interstate 90-94, landing at a three-story apartment building on Summit Avenue with tall white pillars next to a brownstone where F. Scott Fitzgerald once lived. I had been hired away from the Wisconsin Arts Board by the Minnesota State Arts Board to run their Art in Public Places program. The office was just down the street in the old Burbank-Livingston-Griggs home, a grand but tired Italianate mansion in the care of the Historical Society.

I worked there with the finest group of people of my career. Committed to art and artists, ethically aware, intellectually curious and striving, they were also fun to be around. Office rituals included celebrating everyone’s birthday, and with a staff of 17, that meant several celebrations each month.

The most rewarding part of my tenure was traveling around the state to wherever the state was constructing a building with one-percent for public art - state offices for departments of transportation or natural resources, state parks, universities and technical colleges (before and after the systems merged), military installations and even correctional facilities as well as major projects like the Minnesota History Center and Judicial Center in Saint Paul. I got to know communities and their residents in Greater Minnesota from Lake Bronson (population 202 in the far northwest corner of the state where our evening meetings were usually pot-lucks offering opportunities for both business and socializing) to Winona; Ely and Duluth to Worthington; and places in between.

In ten years, I learned more about the state’s people, towns and varied landscapes than many who have grown up here. I saw places with fresh eyes and frequently carried my Hasselblad camera, drawn to photograph the vernacular visual expressions that made places unique and memorable – idiosyncratic individual visions like yard art or holiday displays, visually arresting local business signage and storefronts, some in still-lively downtowns and others, far out in the countryside. (Local artists usually alerted me to the more remote examples, annotating my dog-eared copy of the Minnesota DeLorme Atlas & Gazetteer.)

Aubin’s Photo, Hibbing, Minnesota, 1990. A good way to get to know a community was to check out the window display of the town’s photography studio. After 102 years in business, Aubin’s closed in 2009.

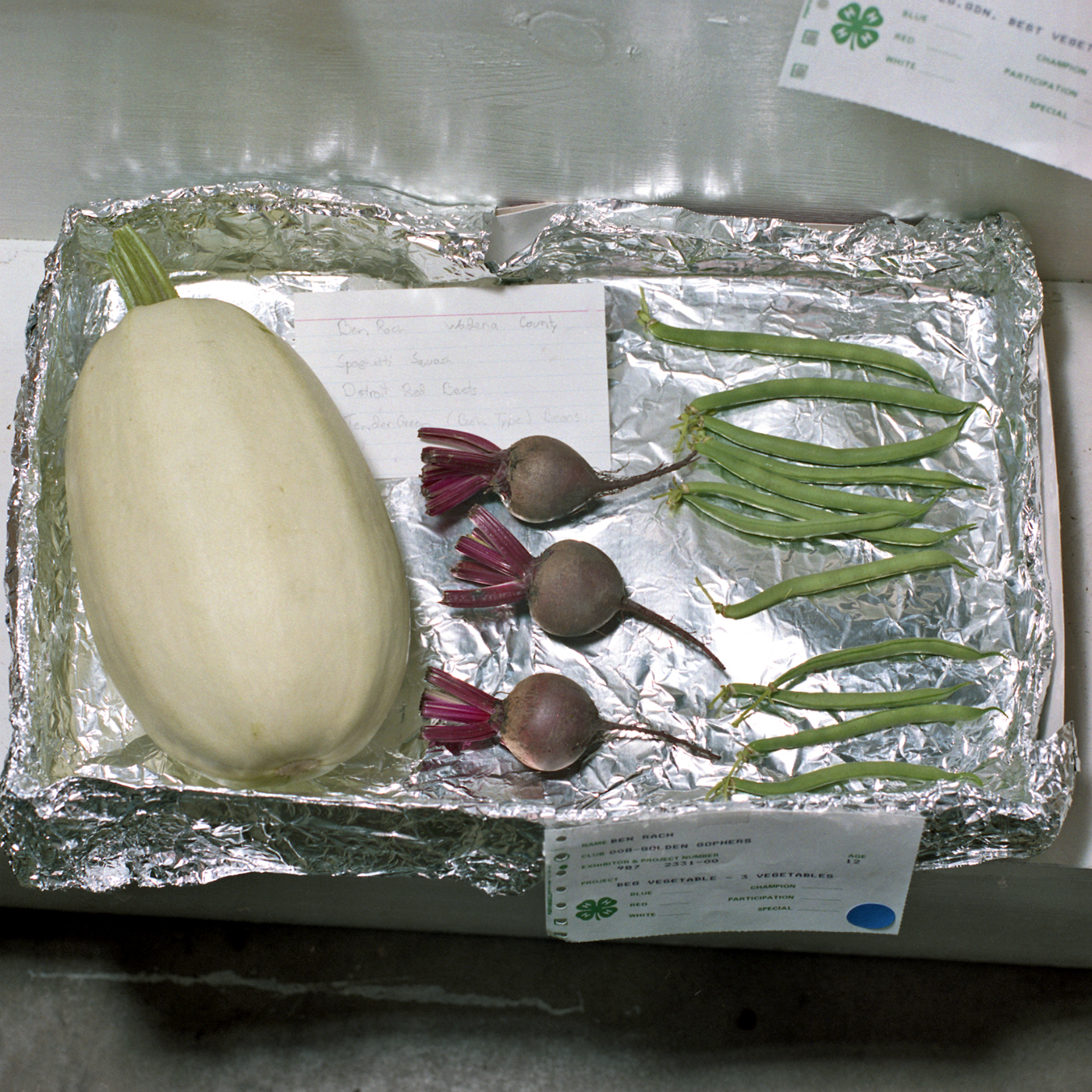

For several years in the early 1990s, I photographed the Wadena County Fair in a rural agricultural area that reminded me of where I grew up in Wisconsin. While working on the public art project for Wadena’s technical college in this town of 4,000 in Central Minnesota, I noticed the community’s beautifully kept fairgrounds shaded by mature trees. I returned on my own that summer and several after to stay at the Brookside Motel, hang out, and explore the 4-H, floral and creative craft displays. I was interested in things made by hand and learned the area was known for the quality of its canning, especially pickles.

I exhibited photographs from the fair and other locations in a pair of solo shows about vernacular visual expressions: “You Can Always See the Obvious” (1995) at Mankato State University’s Conkling Gallery and “Let Us Show You the Unusual” (1996) at the New York Mills Regional Cultural Center, just up Highway 10 from Wadena. The statement I wrote to accompany the show recognizes the tradition of documentary photography, particularly the work of Walker Evans whose images of American life in the 1930s-40s made me aware of the historical importance of the present and what might be passing into history before our eyes.

Scandinavian Mannequin, Jefferson Street, Wadena, Minnesota. May 1990. After the work day, especially in summer when it was light outdoors until around 9 pm, I would walk around town and photograph during this quiet part of the day. I parked my prominently marked state-owned vehicle at a distance otherwise my photographic activity had a tendency to arouse suspicion. I was once mistaken for a state inspector; we had a laugh when I said that I was an arts administrator.

Take A Ride on Sandy, Woolworth’s Store Window, Wadena, Minnesota. May 1990.

In September 1998, I left my post at the Arts Board, returning to graduate school to study landscape architecture, advancing one of my strategies for moving here in the first place – to attend the University of Minnesota, which has landscape architecture, architecture and urban design, and planning programs on the Twin Cities campuses. I subsequently became a licensed landscape architect, and photography continues to be my artistic medium.

In June 2010, an EF4 tornado ripped through Wadena leveling the fairground and its majestic trees, destroying the high school, and damaging a good portion of the new technical college building. Many of the locations shown in my photographs no longer exist; they have passed into history. Buildings have been destroyed or torn down and replaced, businesses closed, and events like the annual Emma Krumbee’s Scarecrow Festival continue but in successive years, the results became too predictable for me to find visually interesting.

My photographs depict a snapshot in time – 1988-1994 – before the existence of Facebook and Instagram and the awareness that almost everything is photographable and shareable. Now different conventions prevail and the kind of originality and idiosyncrasy in these vernacular visual expressions are increasingly rare.

Chun Moo Quan, University Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota, March 1989. Martial arts practitioner executes a high-kick over the reflection of the Wards store tower across the street (torn down and replaced by shopping mall including a Herbergers store, recently closed, T.J. Maxx and Cub Foods).

Automotive Repair Service, Downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota. July 1988. Hand-lettered signage on one-block-square garage that was torn down and replaced by the Saint Thomas University campus.

Automotive Repair Service, Downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota. July 1988. IDS building and the Norwest Tower (now the Wells Fargo Center) reflected in the window.

Fort Road Clark Station, Saint Paul, Minnesota. June 1998. Fort Road is now known as W. 7th Street and this Clark station doesn’t exist.

Fort Road Clark Station, Saint Paul, Minnesota. June 1998

Willy Street Appliance, Madison, Wisconsin. June 1988. This one is in Wisconsin, but it’s too good to leave out.

Miesville Mudhens Field, Minnesota. March 1989. Rural ballpark at the edge of a cornfield known as “Minnesota’s Field of Dreams” before being spruced up for the season. Several years later, my husband Dan and I celebrated our wedding anniversary with a Sunday prime rib dinner at Weiderholt’s Supper Club which has been family-owed for 87 years. I mentioned the special occasion to the wait staff and they surprised us with the gift of a decorated round 9-inch chocolate cake. A WHOLE CHOCOLATE CAKE!

Kowalski’s Red Owl, Grand Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota. March 1989. Last great neon Red Owl sign just before it was de-commissioned. Kowalski’s is in the same location, extensively remodeled.

Cozy Theater, Wadena, Minnesota. May 1990. Art Deco theater in a town of 4,000. Built in 1914 with the neon marquee added in 1938; in continuous operation since.

True Value Hardware, University Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota. February 1989. Faded, painterly signage near hardware store at southwest corner of University and Lexington Avenue, now razed and replaced by the Wilder Foundation complex, Aldi supermarket and White Castle.

True Value Hardware, University Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota. February 1989. Hand-painted billboard.

Paul Bunyan Land, Brainerd, Minnesota. August 1989. Amusement park next to the Paul Bunyan Motel that also included a colossal Paul Bunyan automaton that frightened children by recognizing them by name in a booming voice as they approached. This chicken is eyeing a food trough in line of sight with the coin drop; when I put in a quarter, the chicken pulls a lever that simultaneously releases food... and a postcard.

Emma Krumbee’s Scarecrow Festival, Belle Plaine, Minnesota. October 1993. An evocative sculptural creation.

Front Yard Art, Rural Wadena, Minnesota, July 1992. This pair of images is from an ensemble of weird figures that are open to interpretation…

Front Yard Art, Rural Wadena, Minnesota, July 1992.

Coffee Cup, Vining, Minnesota, June 1996. Metalworker Ken Nyberg applies his curiosity and wit to producing welded scrap metal sculptures that have put tiny Vining, Minnesota (population 78) on the map. His creations grace Nyberg Sculpture Park on Highway 10 and are featured on the website Roadside America.com. Coffee Cup is one of his early works and routinely appeared in local parades.

Aurora Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota. January 1990. Series of modest homes in the Frogtown neighborhood illuminated by Christmas lights still in their display boxes; an efficient method for seasonal decorating!

Aurora Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota. January 1990.